Climate Change Policies & Legislation

Background

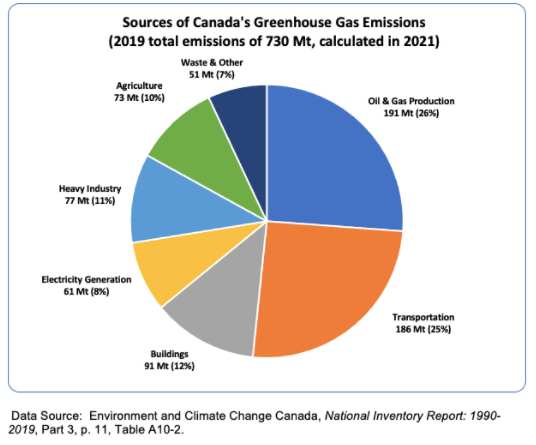

This chart shows the current amounts and sources of Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Most Significant Policies Enacted 2015 – June 2021

1. Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act (GGPPA) (2018)

Applies to all provinces and territories unless a province or territory enact a system of their own that is at least as stringent. As such, it is called the “federal backstop”.

Two Main Components of the GGPPA:

(1) A “fuel charge” on fuels used by consumers that produce greenhouse gasses (GHGs), such as gasoline and natural gas. The charge is imposed at the point of sale, like a tax. More than 80% of the money is returned to Canadians as a “climate action incentive” via their tax returns. The government has announced that, in the future, the money will be returned either by direct bank deposits or cheques.

(2) A charge on GHGs emitted by large industrial facilities (the “Output-Based Pricing System” or “OBPS”). This is a charge on the actual emissions instead of on the fuel. Because the charge would make Canadian products more expensive than foreign imports from countries without a charge, the charge is only on a small amount of the emissions. The government studied the how much GHGs the “cleanest” factories emitted per unit of the various goods produced. It then set up the system so that, depending on the type of goods produced, industry does not pay the charge on between 80% and 95% of the GHGs they emit.

In both cases, the charge is based on a tonne of “carbon dioxide equivalent” (“CO2e”). Together, the scheme is often referred to colloquially as the “carbon tax”.

The carbon tax started at $20 per tonne in 2019 and rose by $10 per year until it is now $40. The government has announced that it will continue to rise at $15 per year until it reaches $170 in 2030.

2. Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act (June 2021)

Requires the government to set an emissions reduction target for 2030, which is fixed at least 40% below Canada’s 2005 emissions. (Canada’s most recent emissions are very close to Canada’s 2005 emissions.) Requires the government to announce an “interim objective” for 2026. Requires the government to establish, by 29 December 2021 (or, with an extension 29 March 2022) a plan to reach the target and objective. Establishes a Net Zero Advisory Body to help advise the government on the plan. Gives the Environment Commissioner some power to evaluate progress toward the target, and whether the target was met. Requires targets and plans for five-year intervals after 2030, until 2050, when the target is “net zero”.

3. Eliminate Coal-fired Electricity Generation by 2030

In many areas of Canada where hydroelectric or nuclear generated electricity is unavailable, coal is burned to create steam to turn turbines in electrical generators. Burning natural gas instead of coal produces much less GHG emissions, but it still creates significant GHG emissions. Jurisdiction is largely provincial, but is covered in the “federal backstop”. Liberal policies and provincial policies enacted to date would eliminate coal-fired generation by 2030, but would replace most of it with natural gas generation.

4. Net-Zero Accelerator Fund

Allocates $8 billion “to decarbonize heavy industry like steel and aluminum, secure Canada’s clean industrial advantage, and create green jobs”. [Quoted from the Liberals’ 2021 election platform book, p. 42. This is significant because new industrial techniques, such as using natural gas or hydrogen instead of coking coal to strip the oxygen from iron ore reduces significant GHGs, but is an expensive and economically risky to “first movers” in private industry. It is one of the few instances where the government spending money is the most effective way to address a specific climate change issue.

5. Methane Regulations

Methane is about 80 times more damaging as a GHG than carbon dioxide. In other words, 1 Mt methane = 80 Mt CO2. Thus 1 Mt methane = 80 Mt CO2e. The Liberal government has already implemented regulations to require oil and gas companies to reduce their methane emissions by 40 to 45% by 2025, relative to 2012 emissions.

6. Climate Change Offset Credit Regulations

The Greenhouse Gas Offset Credit System Regulations (Canada) were published in draft form for comment in March 2021. The comment period is now closed. Environment and Climate Change Canada expects to publish the final regulations in the fall of 2021.

Offsets, which are sometimes called “carbon offsets”, are a system by which a polluter that would otherwise have to pay the carbon tax for its GHG emissions can instead purchase “offset credits”, by which it gives money to someone else who purports to reduce GHG emissions by taking certain actions. A simple example would be a polluter paying money to purchase “offset credits” to someone who promises to use the money to plant a certain number of trees. Presumably, those trees will capture a certain amount of GHGs. The offset credits will trade on a market and the price will fluctuate, depending on how much polluters are willing to pay for them.

The initial four project types that Canada’s Offset Credit System will cover are: advanced refrigeration systems; landfill methane management; improved forest management; and enhanced soil organic carbon.

Offset credit systems are very controversial. A primary reason for this is because the person (or company) taking the “good” action to reduce GHGs might have taken the action anyway, without the offset money. For example, a logging company might have replanted a clear-cut area in order to have trees to cut again in the future. Another reason is that perhaps the person or company taking the action should have been obliged by regulation to take the action anyway. For example, perhaps the logging company should be obliged to replant the land it clear-cut, not rewarded for doing so. Yet another reason is that it is extremely hard to determine whether the supposedly “good” action reduced the same or more amount of GHGs as the “bad” action emitted. Some studies have suggested that the “good” actions seldom make up for the emissions of the “bad” actions.

Critics sometimes compare offset credit systems to the medieval Catholic Church practice of Indulgences. A simple example of an Indulgence would be to imagine a rich man and woman who wanted to have sexual relations, but were married to other people. The sin of adultery would send them both to Hell. To avoid going to Hell, they could each pay the Church a certain amount of money and be granted forgiveness, or an “Indulgence,” before the fact.

The carbon offsets issue has not received much attention from those concerned about climate change in Canada. It almost certainly merits more attention.